Writing Distributed Applications with PyTorch¶

Author: Séb Arnold

Note

View the source code for this tutorial in github.

Prerequisites:

In this short tutorial, we will be going over the distributed package of PyTorch. We’ll see how to set up the distributed setting, use the different communication strategies, and go over some of the internals of the package.

Setup¶

The distributed package included in PyTorch (i.e.,

torch.distributed) enables researchers and practitioners to easily

parallelize their computations across processes and clusters of

machines. To do so, it leverages message passing semantics

allowing each process to communicate data to any of the other processes.

As opposed to the multiprocessing (torch.multiprocessing) package,

processes can use different communication backends and are not

restricted to being executed on the same machine.

In order to get started we need the ability to run multiple processes simultaneously. If you have access to compute cluster you should check with your local sysadmin or use your favorite coordination tool (e.g., pdsh, clustershell, or others). For the purpose of this tutorial, we will use a single machine and fork multiple processes using the following template.

"""run.py:"""

#!/usr/bin/env python

import os

import torch

import torch.distributed as dist

import torch.multiprocessing as mp

def run(rank, size):

""" Distributed function to be implemented later. """

pass

def init_process(rank, size, fn, backend='gloo'):

""" Initialize the distributed environment. """

os.environ['MASTER_ADDR'] = '127.0.0.1'

os.environ['MASTER_PORT'] = '29500'

dist.init_process_group(backend, rank=rank, world_size=size)

fn(rank, size)

if __name__ == "__main__":

size = 2

processes = []

mp.set_start_method("spawn")

for rank in range(size):

p = mp.Process(target=init_process, args=(rank, size, run))

p.start()

processes.append(p)

for p in processes:

p.join()

The above script spawns two processes who will each setup the

distributed environment, initialize the process group

(dist.init_process_group), and finally execute the given run

function.

Let’s have a look at the init_process function. It ensures that

every process will be able to coordinate through a master, using the

same ip address and port. Note that we used the gloo backend but

other backends are available. (c.f.

Section 5.1) We will go over the magic

happening in dist.init_process_group at the end of this tutorial,

but it essentially allows processes to communicate with each other by

sharing their locations.

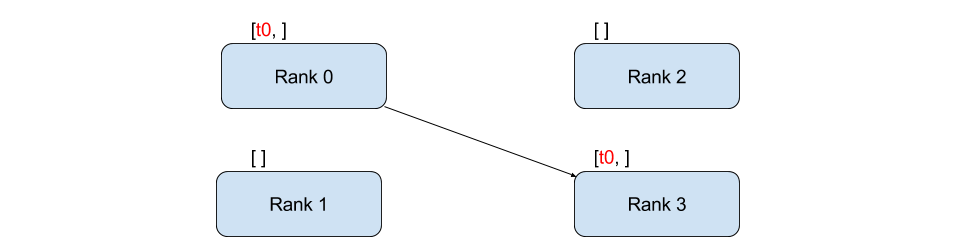

Point-to-Point Communication¶

A transfer of data from one process to another is called a

point-to-point communication. These are achieved through the send

and recv functions or their immediate counter-parts, isend and

irecv.

"""Blocking point-to-point communication."""

def run(rank, size):

tensor = torch.zeros(1)

if rank == 0:

tensor += 1

# Send the tensor to process 1

dist.send(tensor=tensor, dst=1)

else:

# Receive tensor from process 0

dist.recv(tensor=tensor, src=0)

print('Rank ', rank, ' has data ', tensor[0])

In the above example, both processes start with a zero tensor, then process 0 increments the tensor and sends it to process 1 so that they both end up with 1.0. Notice that process 1 needs to allocate memory in order to store the data it will receive.

Also notice that send/recv are blocking: both processes stop

until the communication is completed. On the other hand immediates are

non-blocking; the script continues its execution and the methods

return a Work object upon which we can choose to

wait().

"""Non-blocking point-to-point communication."""

def run(rank, size):

tensor = torch.zeros(1)

req = None

if rank == 0:

tensor += 1

# Send the tensor to process 1

req = dist.isend(tensor=tensor, dst=1)

print('Rank 0 started sending')

else:

# Receive tensor from process 0

req = dist.irecv(tensor=tensor, src=0)

print('Rank 1 started receiving')

req.wait()

print('Rank ', rank, ' has data ', tensor[0])

When using immediates we have to be careful about how we use the sent and received tensors.

Since we do not know when the data will be communicated to the other process,

we should not modify the sent tensor nor access the received tensor before req.wait() has completed.

In other words,

- writing to

tensorafterdist.isend()will result in undefined behaviour. - reading from

tensorafterdist.irecv()will result in undefined behaviour.

However, after req.wait()

has been executed we are guaranteed that the communication took place,

and that the value stored in tensor[0] is 1.0.

Point-to-point communication is useful when we want more fine-grained control over the communication of our processes. They can be used to implement fancy algorithms, such as the one used in Baidu’s DeepSpeech or Facebook’s large-scale experiments.(c.f. Section 4.1)

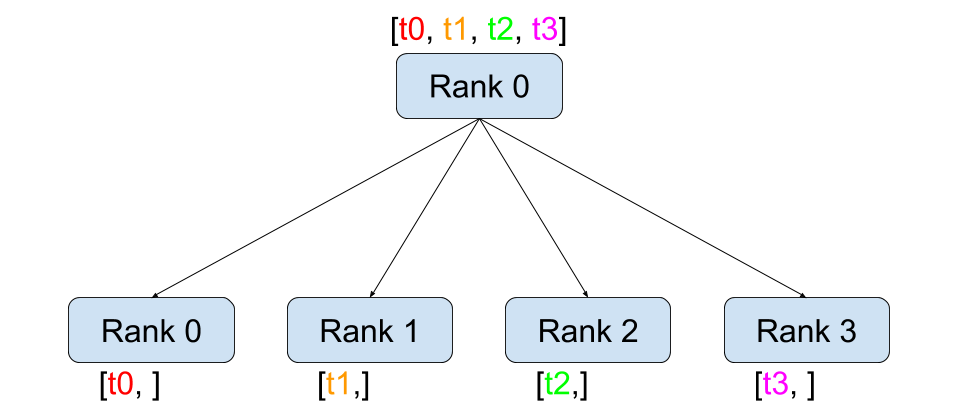

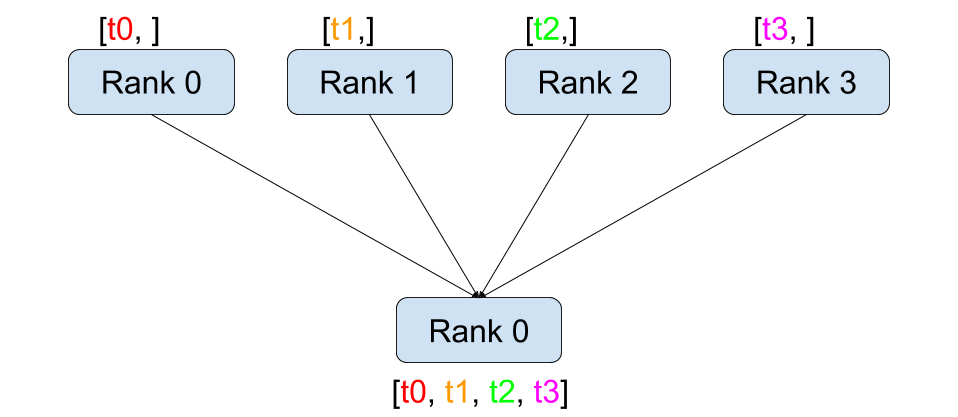

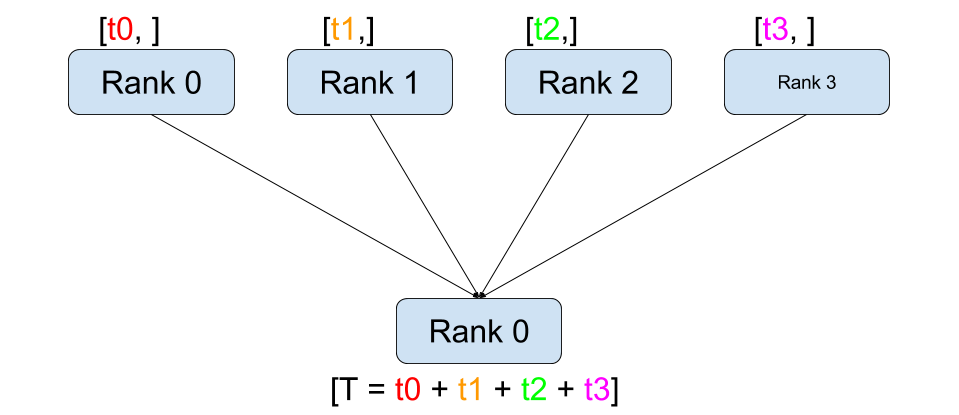

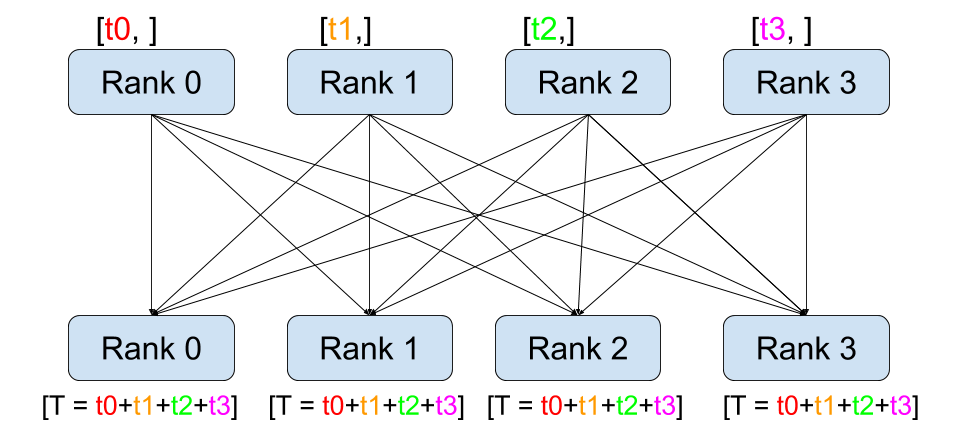

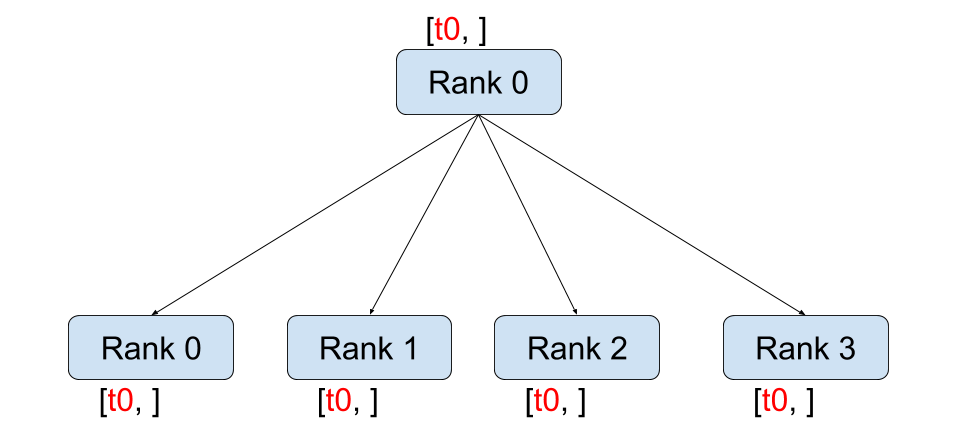

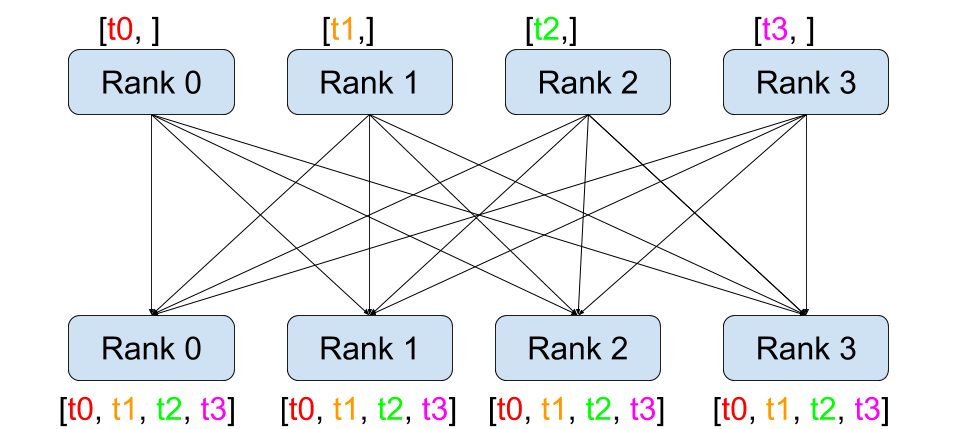

Collective Communication¶

As opposed to point-to-point communcation, collectives allow for

communication patterns across all processes in a group. A group is a

subset of all our processes. To create a group, we can pass a list of

ranks to dist.new_group(group). By default, collectives are executed

on all processes, also known as the world. For example, in order

to obtain the sum of all tensors on all processes, we can use the

dist.all_reduce(tensor, op, group) collective.

""" All-Reduce example."""

def run(rank, size):

""" Simple collective communication. """

group = dist.new_group([0, 1])

tensor = torch.ones(1)

dist.all_reduce(tensor, op=dist.ReduceOp.SUM, group=group)

print('Rank ', rank, ' has data ', tensor[0])

Since we want the sum of all tensors in the group, we use

dist.ReduceOp.SUM as the reduce operator. Generally speaking, any

commutative mathematical operation can be used as an operator.

Out-of-the-box, PyTorch comes with 4 such operators, all working at the

element-wise level:

dist.ReduceOp.SUM,dist.ReduceOp.PRODUCT,dist.ReduceOp.MAX,dist.ReduceOp.MIN.

In addition to dist.all_reduce(tensor, op, group), there are a total

of 6 collectives currently implemented in PyTorch.

dist.broadcast(tensor, src, group): Copiestensorfromsrcto all other processes.dist.reduce(tensor, dst, op, group): Appliesopto everytensorand stores the result indst.dist.all_reduce(tensor, op, group): Same as reduce, but the result is stored in all processes.dist.scatter(tensor, scatter_list, src, group): Copies the \(i^{\text{th}}\) tensorscatter_list[i]to the \(i^{\text{th}}\) process.dist.gather(tensor, gather_list, dst, group): Copiestensorfrom all processes indst.dist.all_gather(tensor_list, tensor, group): Copiestensorfrom all processes totensor_list, on all processes.dist.barrier(group): Blocks all processes in group until each one has entered this function.

Distributed Training¶

Note: You can find the example script of this section in this GitHub repository.

Now that we understand how the distributed module works, let us write something useful with it. Our goal will be to replicate the functionality of DistributedDataParallel. Of course, this will be a didactic example and in a real-world situation you should use the official, well-tested and well-optimized version linked above.

Quite simply we want to implement a distributed version of stochastic gradient descent. Our script will let all processes compute the gradients of their model on their batch of data and then average their gradients. In order to ensure similar convergence results when changing the number of processes, we will first have to partition our dataset. (You could also use tnt.dataset.SplitDataset, instead of the snippet below.)

""" Dataset partitioning helper """

class Partition(object):

def __init__(self, data, index):

self.data = data

self.index = index

def __len__(self):

return len(self.index)

def __getitem__(self, index):

data_idx = self.index[index]

return self.data[data_idx]

class DataPartitioner(object):

def __init__(self, data, sizes=[0.7, 0.2, 0.1], seed=1234):

self.data = data

self.partitions = []

rng = Random()

rng.seed(seed)

data_len = len(data)

indexes = [x for x in range(0, data_len)]

rng.shuffle(indexes)

for frac in sizes:

part_len = int(frac * data_len)

self.partitions.append(indexes[0:part_len])

indexes = indexes[part_len:]

def use(self, partition):

return Partition(self.data, self.partitions[partition])

With the above snippet, we can now simply partition any dataset using the following few lines:

""" Partitioning MNIST """

def partition_dataset():

dataset = datasets.MNIST('./data', train=True, download=True,

transform=transforms.Compose([

transforms.ToTensor(),

transforms.Normalize((0.1307,), (0.3081,))

]))

size = dist.get_world_size()

bsz = 128 / float(size)

partition_sizes = [1.0 / size for _ in range(size)]

partition = DataPartitioner(dataset, partition_sizes)

partition = partition.use(dist.get_rank())

train_set = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(partition,

batch_size=bsz,

shuffle=True)

return train_set, bsz

Assuming we have 2 replicas, then each process will have a train_set

of 60000 / 2 = 30000 samples. We also divide the batch size by the

number of replicas in order to maintain the overall batch size of 128.

We can now write our usual forward-backward-optimize training code, and add a function call to average the gradients of our models. (The following is largely inspired by the official PyTorch MNIST example.)

""" Distributed Synchronous SGD Example """

def run(rank, size):

torch.manual_seed(1234)

train_set, bsz = partition_dataset()

model = Net()

optimizer = optim.SGD(model.parameters(),

lr=0.01, momentum=0.5)

num_batches = ceil(len(train_set.dataset) / float(bsz))

for epoch in range(10):

epoch_loss = 0.0

for data, target in train_set:

optimizer.zero_grad()

output = model(data)

loss = F.nll_loss(output, target)

epoch_loss += loss.item()

loss.backward()

average_gradients(model)

optimizer.step()

print('Rank ', dist.get_rank(), ', epoch ',

epoch, ': ', epoch_loss / num_batches)

It remains to implement the average_gradients(model) function, which

simply takes in a model and averages its gradients across the whole

world.

""" Gradient averaging. """

def average_gradients(model):

size = float(dist.get_world_size())

for param in model.parameters():

dist.all_reduce(param.grad.data, op=dist.ReduceOp.SUM)

param.grad.data /= size

Et voilà! We successfully implemented distributed synchronous SGD and could train any model on a large computer cluster.

Note: While the last sentence is technically true, there are a lot more tricks required to implement a production-level implementation of synchronous SGD. Again, use what has been tested and optimized.

Our Own Ring-Allreduce¶

As an additional challenge, imagine that we wanted to implement DeepSpeech’s efficient ring allreduce. This is fairly easy to implement using point-to-point collectives.

""" Implementation of a ring-reduce with addition. """

def allreduce(send, recv):

rank = dist.get_rank()

size = dist.get_world_size()

send_buff = send.clone()

recv_buff = send.clone()

accum = send.clone()

left = ((rank - 1) + size) % size

right = (rank + 1) % size

for i in range(size - 1):

if i % 2 == 0:

# Send send_buff

send_req = dist.isend(send_buff, right)

dist.recv(recv_buff, left)

accum[:] += recv_buff[:]

else:

# Send recv_buff

send_req = dist.isend(recv_buff, right)

dist.recv(send_buff, left)

accum[:] += send_buff[:]

send_req.wait()

recv[:] = accum[:]

In the above script, the allreduce(send, recv) function has a

slightly different signature than the ones in PyTorch. It takes a

recv tensor and will store the sum of all send tensors in it. As

an exercise left to the reader, there is still one difference between

our version and the one in DeepSpeech: their implementation divides the

gradient tensor into chunks, so as to optimally utilize the

communication bandwidth. (Hint:

torch.chunk)

Advanced Topics¶

We are now ready to discover some of the more advanced functionalities

of torch.distributed. Since there is a lot to cover, this section is

divided into two subsections:

- Communication Backends: where we learn how to use MPI and Gloo for GPU-GPU communication.

- Initialization Methods: where we understand how to best set up the

initial coordination phase in

dist.init_process_group().

Communication Backends¶

One of the most elegant aspects of torch.distributed is its ability

to abstract and build on top of different backends. As mentioned before,

there are currently three backends implemented in PyTorch: Gloo, NCCL, and

MPI. They each have different specifications and tradeoffs, depending

on the desired use case. A comparative table of supported functions can

be found

here.

Gloo Backend

So far we have made extensive usage of the Gloo backend. It is quite handy as a development platform, as it is included in the pre-compiled PyTorch binaries and works on both Linux (since 0.2) and macOS (since 1.3). It supports all point-to-point and collective operations on CPU, and all collective operations on GPU. The implementation of the collective operations for CUDA tensors is not as optimized as the ones provided by the NCCL backend.

As you have surely noticed, our

distributed SGD example does not work if you put model on the GPU.

In order to use multiple GPUs, let us also make the following

modifications:

- Use

device = torch.device("cuda:{}".format(rank)) model = Net()\(\rightarrow\)model = Net().to(device)- Use

data, target = data.to(device), target.to(device)

With the above modifications, our model is now training on two GPUs and

you can monitor their utilization with watch nvidia-smi.

MPI Backend

The Message Passing Interface (MPI) is a standardized tool from the

field of high-performance computing. It allows to do point-to-point and

collective communications and was the main inspiration for the API of

torch.distributed. Several implementations of MPI exist (e.g.

Open-MPI,

MVAPICH2, Intel

MPI) each

optimized for different purposes. The advantage of using the MPI backend

lies in MPI’s wide availability - and high-level of optimization - on

large computer clusters. Some

recent

implementations are also able to take

advantage of CUDA IPC and GPU Direct technologies in order to avoid

memory copies through the CPU.

Unfortunately, PyTorch’s binaries cannot include an MPI implementation and we’ll have to recompile it by hand. Fortunately, this process is fairly simple given that upon compilation, PyTorch will look by itself for an available MPI implementation. The following steps install the MPI backend, by installing PyTorch from source.

- Create and activate your Anaconda environment, install all the

pre-requisites following the

guide, but do

not run

python setup.py installyet. - Choose and install your favorite MPI implementation. Note that

enabling CUDA-aware MPI might require some additional steps. In our

case, we’ll stick to Open-MPI without GPU support:

conda install -c conda-forge openmpi - Now, go to your cloned PyTorch repo and execute

python setup.py install.

In order to test our newly installed backend, a few modifications are required.

- Replace the content under

if __name__ == '__main__':withinit_process(0, 0, run, backend='mpi'). - Run

mpirun -n 4 python myscript.py.

The reason for these changes is that MPI needs to create its own

environment before spawning the processes. MPI will also spawn its own

processes and perform the handshake described in Initialization

Methods, making the rankand size

arguments of init_process_group superfluous. This is actually quite

powerful as you can pass additional arguments to mpirun in order to

tailor computational resources for each process. (Things like number of

cores per process, hand-assigning machines to specific ranks, and some

more)

Doing so, you should obtain the same familiar output as with the other

communication backends.

NCCL Backend

The NCCL backend provides an optimized implementation of collective operations against CUDA tensors. If you only use CUDA tensors for your collective operations, consider using this backend for the best in class performance. The NCCL backend is included in the pre-built binaries with CUDA support.

Initialization Methods¶

To finish this tutorial, let’s talk about the very first function we

called: dist.init_process_group(backend, init_method). In

particular, we will go over the different initialization methods which

are responsible for the initial coordination step between each process.

Those methods allow you to define how this coordination is done.

Depending on your hardware setup, one of these methods should be

naturally more suitable than the others. In addition to the following

sections, you should also have a look at the official

documentation.

Environment Variable

We have been using the environment variable initialization method throughout this tutorial. By setting the following four environment variables on all machines, all processes will be able to properly connect to the master, obtain information about the other processes, and finally handshake with them.

MASTER_PORT: A free port on the machine that will host the process with rank 0.MASTER_ADDR: IP address of the machine that will host the process with rank 0.WORLD_SIZE: The total number of processes, so that the master knows how many workers to wait for.RANK: Rank of each process, so they will know whether it is the master of a worker.

Shared File System

The shared filesystem requires all processes to have access to a shared file system, and will coordinate them through a shared file. This means that each process will open the file, write its information, and wait until everybody did so. After that all required information will be readily available to all processes. In order to avoid race conditions, the file system must support locking through fcntl.

dist.init_process_group(

init_method='file:///mnt/nfs/sharedfile',

rank=args.rank,

world_size=4)

TCP

Initializing via TCP can be achieved by providing the IP address of the process with rank 0 and a reachable port number. Here, all workers will be able to connect to the process with rank 0 and exchange information on how to reach each other.

dist.init_process_group(

init_method='tcp://10.1.1.20:23456',

rank=args.rank,

world_size=4)

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the PyTorch developers for doing such a good job on their implementation, documentation, and tests. When the code was unclear, I could always count on the docs or the tests to find an answer. In particular, I’d like to thank Soumith Chintala, Adam Paszke, and Natalia Gimelshein for providing insightful comments and answering questions on early drafts.