Using the PyTorch C++ Frontend¶

The PyTorch C++ frontend is a pure C++ interface to the PyTorch machine learning framework. While the primary interface to PyTorch naturally is Python, this Python API sits atop a substantial C++ codebase providing foundational data structures and functionality such as tensors and automatic differentiation. The C++ frontend exposes a pure C++11 API that extends this underlying C++ codebase with tools required for machine learning training and inference. This includes a built-in collection of common components for neural network modeling; an API to extend this collection with custom modules; a library of popular optimization algorithms such as stochastic gradient descent; a parallel data loader with an API to define and load datasets; serialization routines and more.

This tutorial will walk you through an end-to-end example of training a model with the C++ frontend. Concretely, we will be training a DCGAN – a kind of generative model – to generate images of MNIST digits. While conceptually a simple example, it should be enough to give you a whirlwind overview of the PyTorch C++ frontend and wet your appetite for training more complex models. We will begin with some motivating words for why you would want to use the C++ frontend to begin with, and then dive straight into defining and training our model.

Tip

Watch this lightning talk from CppCon 2018 for a quick (and humorous) presentation on the C++ frontend.

Tip

This note provides a sweeping overview of the C++ frontend’s components and design philosophy.

Tip

Documentation for the PyTorch C++ ecosystem is available at https://pytorch.org/cppdocs. There you can find high level descriptions as well as API-level documentation.

Motivation¶

Before we embark on our exciting journey of GANs and MNIST digits, let’s take a step back and discuss why you would want to use the C++ frontend instead of the Python one to begin with. We (the PyTorch team) created the C++ frontend to enable research in environments in which Python cannot be used, or is simply not the right tool for the job. Examples for such environments include:

- Low Latency Systems: You may want to do reinforcement learning research in a pure C++ game engine with high frames-per-second and low latency requirements. Using a pure C++ library is a much better fit to such an environment than a Python library. Python may not be tractable at all because of the slowness of the Python interpreter.

- Highly Multithreaded Environments: Due to the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), Python cannot run more than one system thread at a time. Multiprocessing is an alternative, but not as scalable and has significant shortcomings. C++ has no such constraints and threads are easy to use and create. Models requiring heavy parallelization, like those used in Deep Neuroevolution, can benefit from this.

- Existing C++ Codebases: You may be the owner of an existing C++ application doing anything from serving web pages in a backend server to rendering 3D graphics in photo editing software, and wish to integrate machine learning methods into your system. The C++ frontend allows you to remain in C++ and spare yourself the hassle of binding back and forth between Python and C++, while retaining much of the flexibility and intuitiveness of the traditional PyTorch (Python) experience.

The C++ frontend is not intended to compete with the Python frontend. It is meant to complement it. We know researchers and engineers alike love PyTorch for its simplicity, flexibility and intuitive API. Our goal is to make sure you can take advantage of these core design principles in every possible environment, including the ones described above. If one of these scenarios describes your use case well, or if you are simply interested or curious, follow along as we explore the C++ frontend in detail in the following paragraphs.

Tip

The C++ frontend tries to provide an API as close as possible to that of the Python frontend. If you are experienced with the Python frontend and ever ask yourself “how do I do X with the C++ frontend?”, write your code the way you would in Python, and more often than not the same functions and methods will be available in C++ as in Python (just remember to replace dots with double colons).

Writing a Basic Application¶

Let’s begin by writing a minimal C++ application to verify that we’re on the same page regarding our setup and build environment. First, you will need to grab a copy of the LibTorch distribution – our ready-built zip archive that packages all relevant headers, libraries and CMake build files required to use the C++ frontend. The LibTorch distribution is available for download on the PyTorch website for Linux, MacOS and Windows. The rest of this tutorial will assume a basic Ubuntu Linux environment, however you are free to follow along on MacOS or Windows too.

Tip

The note on Installing C++ Distributions of PyTorch describes the following steps in more detail.

Tip

On Windows, debug and release builds are not ABI-compatible. If you plan to

build your project in debug mode, please try the debug version of LibTorch.

Also, make sure you specify the correct configuration in the cmake --build .

line below.

The first step is to download the LibTorch distribution locally, via the link retrieved from the PyTorch website. For a vanilla Ubuntu Linux environment, this means running:

# If you need e.g. CUDA 9.0 support, please replace "cpu" with "cu90" in the URL below.

wget https://download.pytorch.org/libtorch/nightly/cpu/libtorch-shared-with-deps-latest.zip

unzip libtorch-shared-with-deps-latest.zip

Next, let’s write a tiny C++ file called dcgan.cpp that includes

torch/torch.h and for now simply prints out a three by three identity

matrix:

#include <torch/torch.h>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

torch::Tensor tensor = torch::eye(3);

std::cout << tensor << std::endl;

}

To build this tiny application as well as our full-fledged training script later

on we’ll use this CMakeLists.txt file:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.0 FATAL_ERROR)

project(dcgan)

find_package(Torch REQUIRED)

add_executable(dcgan dcgan.cpp)

target_link_libraries(dcgan "${TORCH_LIBRARIES}")

set_property(TARGET dcgan PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD 14)

Note

While CMake is the recommended build system for LibTorch, it is not a hard requirement. You can also use Visual Studio project files, QMake, plain Makefiles or any other build environment you feel comfortable with. However, we do not provide out-of-the-box support for this.

Make note of line 4 in the above CMake file: find_package(Torch REQUIRED).

This instructs CMake to find the build configuration for the LibTorch library.

In order for CMake to know where to find these files, we must set the

CMAKE_PREFIX_PATH when invoking cmake. Before we do this, let’s agree on

the following directory structure for our dcgan application:

dcgan/

CMakeLists.txt

dcgan.cpp

Further, I will refer to the path to the unzipped LibTorch distribution as

/path/to/libtorch. Note that this must be an absolute path. In

particular, setting CMAKE_PREFIX_PATH to something like ../../libtorch

will break in unexpected ways. Instead, write $PWD/../../libtorch to get the

corresponding absolute path. Now, we are ready to build our application:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home# mkdir build

root@fa350df05ecf:/home# cd build

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# cmake -DCMAKE_PREFIX_PATH=/path/to/libtorch ..

-- The C compiler identification is GNU 5.4.0

-- The CXX compiler identification is GNU 5.4.0

-- Check for working C compiler: /usr/bin/cc

-- Check for working C compiler: /usr/bin/cc -- works

-- Detecting C compiler ABI info

-- Detecting C compiler ABI info - done

-- Detecting C compile features

-- Detecting C compile features - done

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++

-- Check for working CXX compiler: /usr/bin/c++ -- works

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info

-- Detecting CXX compiler ABI info - done

-- Detecting CXX compile features

-- Detecting CXX compile features - done

-- Looking for pthread.h

-- Looking for pthread.h - found

-- Looking for pthread_create

-- Looking for pthread_create - not found

-- Looking for pthread_create in pthreads

-- Looking for pthread_create in pthreads - not found

-- Looking for pthread_create in pthread

-- Looking for pthread_create in pthread - found

-- Found Threads: TRUE

-- Found torch: /path/to/libtorch/lib/libtorch.so

-- Configuring done

-- Generating done

-- Build files have been written to: /home/build

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# cmake --build . --config Release

Scanning dependencies of target dcgan

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/dcgan.dir/dcgan.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable dcgan

[100%] Built target dcgan

Above, we first created a build folder inside of our dcgan directory,

entered this folder, ran the cmake command to generate the necessary build

(Make) files and finally compiled the project successfully by running cmake

--build . --config Release. We are now all set to execute our minimal binary

and complete this section on basic project configuration:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# ./dcgan

1 0 0

0 1 0

0 0 1

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{3,3} ]

Looks like an identity matrix to me!

Defining the Neural Network Models¶

Now that we have our basic environment configured, we can dive into the much more interesting parts of this tutorial. First, we will discuss how to define and interact with modules in the C++ frontend. We’ll begin with basic, small-scale example modules and then implement a full-fledged GAN using the extensive library of built-in modules provided by the C++ frontend.

Module API Basics¶

In line with the Python interface, neural networks based on the C++ frontend are

composed of reusable building blocks called modules. There is a base module

class from which all other modules are derived. In Python, this class is

torch.nn.Module and in C++ it is torch::nn::Module. Besides a

forward() method that implements the algorithm the module encapsulates, a

module usually contains any of three kinds of sub-objects: parameters, buffers

and submodules.

Parameters and buffers store state in form of tensors. Parameters record gradients, while buffers do not. Parameters are usually the trainable weights of your neural network. Examples of buffers include means and variances for batch normalization. In order to re-use particular blocks of logic and state, the PyTorch API allows modules to be nested. A nested module is termed a submodule.

Parameters, buffers and submodules must be explicitly registered. Once

registered, methods like parameters() or buffers() can be used to

retrieve a container of all parameters in the entire (nested) module hierarchy.

Similarly, methods like to(...), where e.g. to(torch::kCUDA) moves all

parameters and buffers from CPU to CUDA memory, work on the entire module

hierarchy.

Defining a Module and Registering Parameters¶

To put these words into code, let’s consider this simple module written in the Python interface:

import torch

class Net(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, N, M):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.W = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.randn(N, M))

self.b = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.randn(M))

def forward(self, input):

return torch.addmm(self.b, input, self.W)

In C++, it would look like this:

#include <torch/torch.h>

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {

Net(int64_t N, int64_t M) {

W = register_parameter("W", torch::randn({N, M}));

b = register_parameter("b", torch::randn(M));

}

torch::Tensor forward(torch::Tensor input) {

return torch::addmm(b, input, W);

}

torch::Tensor W, b;

};

Just like in Python, we define a class called Net (for simplicity here a

struct instead of a class) and derive it from the module base class.

Inside the constructor, we create tensors using torch::randn just like we

use torch.randn in Python. One interesting difference is how we register the

parameters. In Python, we wrap the tensors with the torch.nn.Parameter

class, while in C++ we have to pass the tensor through the

register_parameter method instead. The reason for this is that the Python

API can detect that an attribute is of type torch.nn.Parameter and

automatically registers such tensors. In C++, reflection is very limited, so a

more traditional (and less magical) approach is provided.

Registering Submodules and Traversing the Module Hierarchy¶

In the same way we can register parameters, we can also register submodules. In Python, submodules are automatically detected and registered when they are assigned as an attribute of a module:

class Net(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, N, M):

super(Net, self).__init__()

# Registered as a submodule behind the scenes

self.linear = torch.nn.Linear(N, M)

self.another_bias = torch.nn.Parameter(torch.rand(M))

def forward(self, input):

return self.linear(input) + self.another_bias

This allows, for example, to use the parameters() method to recursively

access all parameters in our module hierarchy:

>>> net = Net(4, 5)

>>> print(list(net.parameters()))

[Parameter containing:

tensor([0.0808, 0.8613, 0.2017, 0.5206, 0.5353], requires_grad=True), Parameter containing:

tensor([[-0.3740, -0.0976, -0.4786, -0.4928],

[-0.1434, 0.4713, 0.1735, -0.3293],

[-0.3467, -0.3858, 0.1980, 0.1986],

[-0.1975, 0.4278, -0.1831, -0.2709],

[ 0.3730, 0.4307, 0.3236, -0.0629]], requires_grad=True), Parameter containing:

tensor([ 0.2038, 0.4638, -0.2023, 0.1230, -0.0516], requires_grad=True)]

To register submodules in C++, use the aptly named register_module() method

to register a module like torch::nn::Linear:

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {

Net(int64_t N, int64_t M)

: linear(register_module("linear", torch::nn::Linear(N, M))) {

another_bias = register_parameter("b", torch::randn(M));

}

torch::Tensor forward(torch::Tensor input) {

return linear(input) + another_bias;

}

torch::nn::Linear linear;

torch::Tensor another_bias;

};

Tip

You can find the full list of available built-in modules like

torch::nn::Linear, torch::nn::Dropout or torch::nn::Conv2d in the

documentation of the torch::nn namespace here.

One subtlety about the above code is why the submodule was created in the

constructor’s initializer list, while the parameter was created inside the

constructor body. There is a good reason for this, which we’ll touch upon this

in the section on the C++ frontend’s ownership model further below. The end

result, however, is that we can recursively access our module tree’s parameters

just like in Python. Calling parameters() returns a

std::vector<torch::Tensor>, which we can iterate over:

int main() {

Net net(4, 5);

for (const auto& p : net.parameters()) {

std::cout << p << std::endl;

}

}

which prints:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# ./dcgan

0.0345

1.4456

-0.6313

-0.3585

-0.4008

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5} ]

-0.1647 0.2891 0.0527 -0.0354

0.3084 0.2025 0.0343 0.1824

-0.4630 -0.2862 0.2500 -0.0420

0.3679 -0.1482 -0.0460 0.1967

0.2132 -0.1992 0.4257 0.0739

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5,4} ]

0.01 *

3.6861

-10.1166

-45.0333

7.9983

-20.0705

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5} ]

with three parameters just like in Python. To also see the names of these

parameters, the C++ API provides a named_parameters() method which returns

an OrderedDict just like in Python:

Net net(4, 5);

for (const auto& pair : net.named_parameters()) {

std::cout << pair.key() << ": " << pair.value() << std::endl;

}

which we can execute again to see the output:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# make && ./dcgan 11:13:48

Scanning dependencies of target dcgan

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/dcgan.dir/dcgan.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable dcgan

[100%] Built target dcgan

b: -0.1863

-0.8611

-0.1228

1.3269

0.9858

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5} ]

linear.weight: 0.0339 0.2484 0.2035 -0.2103

-0.0715 -0.2975 -0.4350 -0.1878

-0.3616 0.1050 -0.4982 0.0335

-0.1605 0.4963 0.4099 -0.2883

0.1818 -0.3447 -0.1501 -0.0215

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5,4} ]

linear.bias: -0.0250

0.0408

0.3756

-0.2149

-0.3636

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{5} ]

Note

The documentation

for torch::nn::Module contains the full list of methods that operate on

the module hierarchy.

Running the Network in Forward Mode¶

To execute the network in C++, we simply call the forward() method we

defined ourselves:

int main() {

Net net(4, 5);

std::cout << net.forward(torch::ones({2, 4})) << std::endl;

}

which prints something like:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# ./dcgan

0.8559 1.1572 2.1069 -0.1247 0.8060

0.8559 1.1572 2.1069 -0.1247 0.8060

[ Variable[CPUFloatType]{2,5} ]

Module Ownership¶

At this point, we know how to define a module in C++, register parameters,

register submodules, traverse the module hierarchy via methods like

parameters() and finally run the module’s forward() method. While there

are many more methods, classes and topics to devour in the C++ API, I will refer

you to docs for

the full menu. We’ll also touch upon some more concepts as we implement the

DCGAN model and end-to-end training pipeline in just a second. Before we do so,

let me briefly touch upon the ownership model the C++ frontend provides for

subclasses of torch::nn::Module.

For this discussion, the ownership model refers to the way modules are stored and passed around – which determines who or what owns a particular module instance. In Python, objects are always allocated dynamically (on the heap) and have reference semantics. This is very easy to work with and straightforward to understand. In fact, in Python, you can largely forget about where objects live and how they get referenced, and focus on getting things done.

C++, being a lower level language, provides more options in this realm. This

increases complexity and heavily influences the design and ergonomics of the C++

frontend. In particular, for modules in the C++ frontend, we have the option of

using either value semantics or reference semantics. The first case is the

simplest and was shown in the examples thus far: module objects are allocated on

the stack and when passed to a function, can be either copied, moved (with

std::move) or taken by reference or by pointer:

struct Net : torch::nn::Module { };

void a(Net net) { }

void b(Net& net) { }

void c(Net* net) { }

int main() {

Net net;

a(net);

a(std::move(net));

b(net);

c(&net);

}

For the second case – reference semantics – we can use std::shared_ptr.

The advantage of reference semantics is that, like in Python, it reduces the

cognitive overhead of thinking about how modules must be passed to functions and

how arguments must be declared (assuming you use shared_ptr everywhere).

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {};

void a(std::shared_ptr<Net> net) { }

int main() {

auto net = std::make_shared<Net>();

a(net);

}

In our experience, researchers coming from dynamic languages greatly prefer

reference semantics over value semantics, even though the latter is more

“native” to C++. It is also important to note that torch::nn::Module’s

design, in order to stay close to the ergonomics of the Python API, relies on

shared ownership. For example, take our earlier (here shortened) definition of

Net:

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {

Net(int64_t N, int64_t M)

: linear(register_module("linear", torch::nn::Linear(N, M)))

{ }

torch::nn::Linear linear;

};

In order to use the linear submodule, we want to store it directly in our

class. However, we also want the module base class to know about and have access

to this submodule. For this, it must store a reference to this submodule. At

this point, we have already arrived at the need for shared ownership. Both the

torch::nn::Module class and concrete Net class require a reference to

the submodule. For this reason, the base class stores modules as

shared_ptrs, and therefore the concrete class must too.

But wait! I don’t see any mention of shared_ptr in the above code! Why is

that? Well, because std::shared_ptr<MyModule> is a hell of a lot to type. To

keep our researchers productive, we came up with an elaborate scheme to hide the

mention of shared_ptr – a benefit usually reserved for value semantics –

while retaining reference semantics. To understand how this works, we can take a

look at a simplified definition of the torch::nn::Linear module in the core

library (the full definition is here):

struct LinearImpl : torch::nn::Module {

LinearImpl(int64_t in, int64_t out);

Tensor forward(const Tensor& input);

Tensor weight, bias;

};

TORCH_MODULE(Linear);

In brief: the module is not called Linear, but LinearImpl. A macro,

TORCH_MODULE then defines the actual Linear class. This “generated”

class is effectively a wrapper over a std::shared_ptr<LinearImpl>. It is a

wrapper instead of a simple typedef so that, among other things, constructors

still work as expected, i.e. you can still write torch::nn::Linear(3, 4)

instead of std::make_shared<LinearImpl>(3, 4). We call the class created by

the macro the module holder. Like with (shared) pointers, you access the

underlying object using the arrow operator (like model->forward(...)). The

end result is an ownership model that resembles that of the Python API quite

closely. Reference semantics become the default, but without the extra typing of

std::shared_ptr or std::make_shared. For our Net, using the module

holder API looks like this:

struct NetImpl : torch::nn::Module {};

TORCH_MODULE(Net);

void a(Net net) { }

int main() {

Net net;

a(net);

}

There is one subtle issue that deserves mention here. A default constructed

std::shared_ptr is “empty”, i.e. contains a null pointer. What is a default

constructed Linear or Net? Well, it’s a tricky choice. We could say it

should be an empty (null) std::shared_ptr<LinearImpl>. However, recall that

Linear(3, 4) is the same as std::make_shared<LinearImpl>(3, 4). This

means that if we had decided that Linear linear; should be a null pointer,

then there would be no way to construct a module that does not take any

constructor arguments, or defaults all of them. For this reason, in the current

API, a default constructed module holder (like Linear()) invokes the

default constructor of the underlying module (LinearImpl()). If the

underlying module does not have a default constructor, you get a compiler error.

To instead construct the empty holder, you can pass nullptr to the

constructor of the holder.

In practice, this means you can use submodules either like shown earlier, where the module is registered and constructed in the initializer list:

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {

Net(int64_t N, int64_t M)

: linear(register_module("linear", torch::nn::Linear(N, M)))

{ }

torch::nn::Linear linear;

};

or you can first construct the holder with a null pointer and then assign to it in the constructor (more familiar for Pythonistas):

struct Net : torch::nn::Module {

Net(int64_t N, int64_t M) {

linear = register_module("linear", torch::nn::Linear(N, M));

}

torch::nn::Linear linear{nullptr}; // construct an empty holder

};

In conclusion: Which ownership model – which semantics – should you use? The

C++ frontend’s API best supports the ownership model provided by module holders.

The only disadvantage of this mechanism is one extra line of boilerplate below

the module declaration. That said, the simplest model is still the value

semantics model shown in the introduction to C++ modules. For small, simple

scripts, you may get away with it too. But you’ll find sooner or later that, for

technical reasons, it is not always supported. For example, the serialization

API (torch::save and torch::load) only supports module holders (or plain

shared_ptr). As such, the module holder API is the recommended way of

defining modules with the C++ frontend, and we will use this API in this

tutorial henceforth.

Defining the DCGAN Modules¶

We now have the necessary background and introduction to define the modules for the machine learning task we want to solve in this post. To recap: our task is to generate images of digits from the MNIST dataset. We want to use a generative adversarial network (GAN) to solve this task. In particular, we’ll use a DCGAN architecture – one of the first and simplest of its kind, but entirely sufficient for this task.

Tip

You can find the full source code presented in this tutorial in this repository.

What was a GAN aGAN?¶

A GAN consists of two distinct neural network models: a generator and a

discriminator. The generator receives samples from a noise distribution, and

its aim is to transform each noise sample into an image that resembles those of

a target distribution – in our case the MNIST dataset. The discriminator in

turn receives either real images from the MNIST dataset, or fake images from

the generator. It is asked to emit a probability judging how real (closer to

1) or fake (closer to 0) a particular image is. Feedback from the

discriminator on how real the images produced by the generator are is used to

train the generator. Feedback on how good of an eye for authenticity the

discriminator has is used to optimize the discriminator. In theory, a delicate

balance between the generator and discriminator makes them improve in tandem,

leading to the generator producing images indistinguishable from the target

distribution, fooling the discriminator’s (by then) excellent eye into emitting

a probability of 0.5 for both real and fake images. For us, the end result

is a machine that receives noise as input and generates realistic images of

digits as its output.

The Generator Module¶

We begin by defining the generator module, which consists of a series of

transposed 2D convolutions, batch normalizations and ReLU activation units.

We explicitly pass inputs (in a functional way) between modules in the

forward() method of a module we define ourselves:

struct DCGANGeneratorImpl : nn::Module {

DCGANGeneratorImpl(int kNoiseSize)

: conv1(nn::ConvTranspose2dOptions(kNoiseSize, 256, 4)

.bias(false)),

batch_norm1(256),

conv2(nn::ConvTranspose2dOptions(256, 128, 3)

.stride(2)

.padding(1)

.bias(false)),

batch_norm2(128),

conv3(nn::ConvTranspose2dOptions(128, 64, 4)

.stride(2)

.padding(1)

.bias(false)),

batch_norm3(64),

conv4(nn::ConvTranspose2dOptions(64, 1, 4)

.stride(2)

.padding(1)

.bias(false))

{

// register_module() is needed if we want to use the parameters() method later on

register_module("conv1", conv1);

register_module("conv2", conv2);

register_module("conv3", conv3);

register_module("conv4", conv4);

register_module("batch_norm1", batch_norm1);

register_module("batch_norm2", batch_norm2);

register_module("batch_norm3", batch_norm3);

}

torch::Tensor forward(torch::Tensor x) {

x = torch::relu(batch_norm1(conv1(x)));

x = torch::relu(batch_norm2(conv2(x)));

x = torch::relu(batch_norm3(conv3(x)));

x = torch::tanh(conv4(x));

return x;

}

nn::ConvTranspose2d conv1, conv2, conv3, conv4;

nn::BatchNorm2d batch_norm1, batch_norm2, batch_norm3;

};

TORCH_MODULE(DCGANGenerator);

DCGANGenerator generator(kNoiseSize);

We can now invoke forward() on the DCGANGenerator to map a noise sample to an image.

The particular modules chosen, like nn::ConvTranspose2d and nn::BatchNorm2d,

follows the structure outlined earlier. The kNoiseSize constant determines

the size of the input noise vector and is set to 100. Hyperparameters were,

of course, found via grad student descent.

Attention

No grad students were harmed in the discovery of hyperparameters. They were fed Soylent regularly.

Note

A brief word on the way options are passed to built-in modules like Conv2d

in the C++ frontend: Every module has some required options, like the number

of features for BatchNorm2d. If you only need to configure the required

options, you can pass them directly to the module’s constructor, like

BatchNorm2d(128) or Dropout(0.5) or Conv2d(8, 4, 2) (for input

channel count, output channel count, and kernel size). If, however, you need

to modify other options, which are normally defaulted, such as bias

for Conv2d, you need to construct and pass an options object. Every

module in the C++ frontend has an associated options struct, called

ModuleOptions where Module is the name of the module, like

LinearOptions for Linear. This is what we do for the Conv2d

modules above.

The Discriminator Module¶

The discriminator is similarly a sequence of convolutions, batch normalizations and activations. However, the convolutions are now regular ones instead of transposed, and we use a leaky ReLU with an alpha value of 0.2 instead of a vanilla ReLU. Also, the final activation becomes a Sigmoid, which squashes values into a range between 0 and 1. We can then interpret these squashed values as the probabilities the discriminator assigns to images being real.

To build the discriminator, we will try something different: a Sequential module. Like in Python, PyTorch here provides two APIs for model definition: a functional one where inputs are passed through successive functions (e.g. the generator module example), and a more object-oriented one where we build a Sequential module containing the entire model as submodules. Using Sequential, the discriminator would look like:

nn::Sequential discriminator(

// Layer 1

nn::Conv2d(

nn::Conv2dOptions(1, 64, 4).stride(2).padding(1).bias(false)),

nn::LeakyReLU(nn::LeakyReLUOptions().negative_slope(0.2)),

// Layer 2

nn::Conv2d(

nn::Conv2dOptions(64, 128, 4).stride(2).padding(1).bias(false)),

nn::BatchNorm2d(128),

nn::LeakyReLU(nn::LeakyReLUOptions().negative_slope(0.2)),

// Layer 3

nn::Conv2d(

nn::Conv2dOptions(128, 256, 4).stride(2).padding(1).bias(false)),

nn::BatchNorm2d(256),

nn::LeakyReLU(nn::LeakyReLUOptions().negative_slope(0.2)),

// Layer 4

nn::Conv2d(

nn::Conv2dOptions(256, 1, 3).stride(1).padding(0).bias(false)),

nn::Sigmoid());

Tip

A Sequential module simply performs function composition. The output of

the first submodule becomes the input of the second, the output of the third

becomes the input of the fourth and so on.

Loading Data¶

Now that we have defined the generator and discriminator model, we need some data we can train these models with. The C++ frontend, like the Python one, comes with a powerful parallel data loader. This data loader can read batches of data from a dataset (which you can define yourself) and provides many configuration knobs.

Note

While the Python data loader uses multi-processing, the C++ data loader is truly multi-threaded and does not launch any new processes.

The data loader is part of the C++ frontend’s data api, contained in the

torch::data:: namespace. This API consists of a few different components:

- The data loader class,

- An API for defining datasets,

- An API for defining transforms, which can be applied to datasets,

- An API for defining samplers, which produce the indices with which datasets are indexed,

- A library of existing datasets, transforms and samplers.

For this tutorial, we can use the MNIST dataset that comes with the C++

frontend. Let’s instantiate a torch::data::datasets::MNIST for this, and

apply two transformations: First, we normalize the images so that they are in

the range of -1 to +1 (from an original range of 0 to 1).

Second, we apply the Stack collation, which takes a batch of tensors and

stacks them into a single tensor along the first dimension:

auto dataset = torch::data::datasets::MNIST("./mnist")

.map(torch::data::transforms::Normalize<>(0.5, 0.5))

.map(torch::data::transforms::Stack<>());

Note that the MNIST dataset should be located in the ./mnist directory

relative to wherever you execute the training binary from. You can use this

script

to download the MNIST dataset.

Next, we create a data loader and pass it this dataset. To make a new data

loader, we use torch::data::make_data_loader, which returns a

std::unique_ptr of the correct type (which depends on the type of the

dataset, the type of the sampler and some other implementation details):

auto data_loader = torch::data::make_data_loader(std::move(dataset));

The data loader does come with a lot of options. You can inspect the full set

here.

For example, to speed up the data loading, we can increase the number of

workers. The default number is zero, which means the main thread will be used.

If we set workers to 2, two threads will be spawned that load data

concurrently. We should also increase the batch size from its default of 1

to something more reasonable, like 64 (the value of kBatchSize). So

let’s create a DataLoaderOptions object and set the appropriate properties:

auto data_loader = torch::data::make_data_loader(

std::move(dataset),

torch::data::DataLoaderOptions().batch_size(kBatchSize).workers(2));

We can now write a loop to load batches of data, which we’ll only print to the console for now:

for (torch::data::Example<>& batch : *data_loader) {

std::cout << "Batch size: " << batch.data.size(0) << " | Labels: ";

for (int64_t i = 0; i < batch.data.size(0); ++i) {

std::cout << batch.target[i].item<int64_t>() << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

The type returned by the data loader in this case is a torch::data::Example.

This type is a simple struct with a data field for the data and a target

field for the label. Because we applied the Stack collation earlier, the

data loader returns only a single such example. If we had not applied the

collation, the data loader would yield std::vector<torch::data::Example<>>

instead, with one element per example in the batch.

If you rebuild and run this code, you should see something like this:

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# make

Scanning dependencies of target dcgan

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/dcgan.dir/dcgan.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable dcgan

[100%] Built target dcgan

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# make

[100%] Built target dcgan

root@fa350df05ecf:/home/build# ./dcgan

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 5 2 6 7 2 1 6 7 0 1 6 2 3 6 9 1 8 4 0 6 5 3 3 0 4 6 6 6 4 0 8 6 0 6 9 2 4 0 2 8 6 3 3 2 9 2 0 1 4 2 3 4 8 2 9 9 3 5 8 0 0 7 9 9

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 2 2 4 7 1 2 8 8 6 9 0 2 2 9 3 6 1 3 8 0 4 4 8 8 8 9 2 6 4 7 1 5 0 9 7 5 4 3 5 4 1 2 8 0 7 1 9 6 1 6 5 3 4 4 1 2 3 2 3 5 0 1 6 2

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 4 5 4 2 1 4 8 3 8 3 6 1 5 4 3 6 2 2 5 1 3 1 5 0 8 2 1 5 3 2 4 4 5 9 7 2 8 9 2 0 6 7 4 3 8 3 5 8 8 3 0 5 8 0 8 7 8 5 5 6 1 7 8 0

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 3 3 7 1 4 1 6 1 0 3 6 4 0 2 5 4 0 4 2 8 1 9 6 5 1 6 3 2 8 9 2 3 8 7 4 5 9 6 0 8 3 0 0 6 4 8 2 5 4 1 8 3 7 8 0 0 8 9 6 7 2 1 4 7

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 3 0 5 5 9 8 3 9 8 9 5 9 5 0 4 1 2 7 7 2 0 0 5 4 8 7 7 6 1 0 7 9 3 0 6 3 2 6 2 7 6 3 3 4 0 5 8 8 9 1 9 2 1 9 4 4 9 2 4 6 2 9 4 0

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 9 6 7 5 3 5 9 0 8 6 6 7 8 2 1 9 8 8 1 1 8 2 0 7 1 4 1 6 7 5 1 7 7 4 0 3 2 9 0 6 6 3 4 4 8 1 2 8 6 9 2 0 3 1 2 8 5 6 4 8 5 8 6 2

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 9 3 0 3 6 5 1 8 6 0 1 9 9 1 6 1 7 7 4 4 4 7 8 8 6 7 8 2 6 0 4 6 8 2 5 3 9 8 4 0 9 9 3 7 0 5 8 2 4 5 6 2 8 2 5 3 7 1 9 1 8 2 2 7

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 9 1 9 2 7 2 6 0 8 6 8 7 7 4 8 6 1 1 6 8 5 7 9 1 3 2 0 5 1 7 3 1 6 1 0 8 6 0 8 1 0 5 4 9 3 8 5 8 4 8 0 1 2 6 2 4 2 7 7 3 7 4 5 3

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 8 8 3 1 8 6 4 2 9 5 8 0 2 8 6 6 7 0 9 8 3 8 7 1 6 6 2 7 7 4 5 5 2 1 7 9 5 4 9 1 0 3 1 9 3 9 8 8 5 3 7 5 3 6 8 9 4 2 0 1 2 5 4 7

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 9 2 7 0 8 4 4 2 7 5 0 0 6 2 0 5 9 5 9 8 8 9 3 5 7 5 4 7 3 0 5 7 6 5 7 1 6 2 8 7 6 3 2 6 5 6 1 2 7 7 0 0 5 9 0 0 9 1 7 8 3 2 9 4

Batch size: 64 | Labels: 7 6 5 7 7 5 2 2 4 9 9 4 8 7 4 8 9 4 5 7 1 2 6 9 8 5 1 2 3 6 7 8 1 1 3 9 8 7 9 5 0 8 5 1 8 7 2 6 5 1 2 0 9 7 4 0 9 0 4 6 0 0 8 6

...

Which means we are successfully able to load data from the MNIST dataset.

Writing the Training Loop¶

Let’s now finish the algorithmic part of our example and implement the delicate dance between the generator and discriminator. First, we’ll create two optimizers, one for the generator and one for the discriminator. The optimizers we use implement the Adam algorithm:

torch::optim::Adam generator_optimizer(

generator->parameters(), torch::optim::AdamOptions(2e-4).beta1(0.5));

torch::optim::Adam discriminator_optimizer(

discriminator->parameters(), torch::optim::AdamOptions(5e-4).beta1(0.5));

Note

As of this writing, the C++ frontend provides optimizers implementing Adagrad, Adam, LBFGS, RMSprop and SGD. The docs have the up-to-date list.

Next, we need to update our training loop. We’ll add an outer loop to exhaust the data loader every epoch and then write the GAN training code:

for (int64_t epoch = 1; epoch <= kNumberOfEpochs; ++epoch) {

int64_t batch_index = 0;

for (torch::data::Example<>& batch : *data_loader) {

// Train discriminator with real images.

discriminator->zero_grad();

torch::Tensor real_images = batch.data;

torch::Tensor real_labels = torch::empty(batch.data.size(0)).uniform_(0.8, 1.0);

torch::Tensor real_output = discriminator->forward(real_images);

torch::Tensor d_loss_real = torch::binary_cross_entropy(real_output, real_labels);

d_loss_real.backward();

// Train discriminator with fake images.

torch::Tensor noise = torch::randn({batch.data.size(0), kNoiseSize, 1, 1});

torch::Tensor fake_images = generator->forward(noise);

torch::Tensor fake_labels = torch::zeros(batch.data.size(0));

torch::Tensor fake_output = discriminator->forward(fake_images.detach());

torch::Tensor d_loss_fake = torch::binary_cross_entropy(fake_output, fake_labels);

d_loss_fake.backward();

torch::Tensor d_loss = d_loss_real + d_loss_fake;

discriminator_optimizer.step();

// Train generator.

generator->zero_grad();

fake_labels.fill_(1);

fake_output = discriminator->forward(fake_images);

torch::Tensor g_loss = torch::binary_cross_entropy(fake_output, fake_labels);

g_loss.backward();

generator_optimizer.step();

std::printf(

"\r[%2ld/%2ld][%3ld/%3ld] D_loss: %.4f | G_loss: %.4f",

epoch,

kNumberOfEpochs,

++batch_index,

batches_per_epoch,

d_loss.item<float>(),

g_loss.item<float>());

}

}

Above, we first evaluate the discriminator on real images, for which it should

assign a high probability. For this, we use

torch::empty(batch.data.size(0)).uniform_(0.8, 1.0) as the target

probabilities.

Note

We pick random values uniformly distributed between 0.8 and 1.0 instead of 1.0 everywhere in order to make the discriminator training more robust. This trick is called label smoothing.

Before evaluating the discriminator, we zero out the gradients of its

parameters. After computing the loss, we back-propagate it through the network by

calling d_loss.backward() to compute new gradients. We repeat this spiel for

the fake images. Instead of using images from the dataset, we let the generator

create fake images for this by feeding it a batch of random noise. We then

forward those fake images to the discriminator. This time, we want the

discriminator to emit low probabilities, ideally all zeros. Once we have

computed the discriminator loss for both the batch of real and the batch of fake

images, we can progress the discriminator’s optimizer by one step in order to

update its parameters.

To train the generator, we again first zero its gradients, and then re-evaluate

the discriminator on the fake images. However, this time we want the

discriminator to assign probabilities very close to one, which would indicate

that the generator can produce images that fool the discriminator into thinking

they are actually real (from the dataset). For this, we fill the fake_labels

tensor with all ones. We finally step the generator’s optimizer to also update

its parameters.

We should now be ready to train our model on the CPU. We don’t have any code yet to capture state or sample outputs, but we’ll add this in just a moment. For now, let’s just observe that our model is doing something – we’ll later verify based on the generated images whether this something is meaningful. Re-building and running should print something like:

root@3c0711f20896:/home/build# make && ./dcgan

Scanning dependencies of target dcgan

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/dcgan.dir/dcgan.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable dcgan

[100%] Built target dcga

[ 1/10][100/938] D_loss: 0.6876 | G_loss: 4.1304

[ 1/10][200/938] D_loss: 0.3776 | G_loss: 4.3101

[ 1/10][300/938] D_loss: 0.3652 | G_loss: 4.6626

[ 1/10][400/938] D_loss: 0.8057 | G_loss: 2.2795

[ 1/10][500/938] D_loss: 0.3531 | G_loss: 4.4452

[ 1/10][600/938] D_loss: 0.3501 | G_loss: 5.0811

[ 1/10][700/938] D_loss: 0.3581 | G_loss: 4.5623

[ 1/10][800/938] D_loss: 0.6423 | G_loss: 1.7385

[ 1/10][900/938] D_loss: 0.3592 | G_loss: 4.7333

[ 2/10][100/938] D_loss: 0.4660 | G_loss: 2.5242

[ 2/10][200/938] D_loss: 0.6364 | G_loss: 2.0886

[ 2/10][300/938] D_loss: 0.3717 | G_loss: 3.8103

[ 2/10][400/938] D_loss: 1.0201 | G_loss: 1.3544

[ 2/10][500/938] D_loss: 0.4522 | G_loss: 2.6545

...

Moving to the GPU¶

While our current script can run just fine on the CPU, we all know convolutions

are a lot faster on GPU. Let’s quickly discuss how we can move our training onto

the GPU. We’ll need to do two things for this: pass a GPU device specification

to tensors we allocate ourselves, and explicitly copy any other tensors onto the

GPU via the to() method all tensors and modules in the C++ frontend have.

The simplest way to achieve both is to create an instance of torch::Device

at the top level of our training script, and then pass that device to tensor

factory functions like torch::zeros as well as the to() method. We can

start by doing this with a CPU device:

// Place this somewhere at the top of your training script.

torch::Device device(torch::kCPU);

New tensor allocations like

torch::Tensor fake_labels = torch::zeros(batch.data.size(0));

should be updated to take the device as the last argument:

torch::Tensor fake_labels = torch::zeros(batch.data.size(0), device);

For tensors whose creation is not in our hands, like those coming from the MNIST

dataset, we must insert explicit to() calls. This means

torch::Tensor real_images = batch.data;

becomes

torch::Tensor real_images = batch.data.to(device);

and also our model parameters should be moved to the correct device:

generator->to(device);

discriminator->to(device);

Note

If a tensor already lives on the device supplied to to(), the call is a

no-op. No extra copy is made.

At this point, we’ve just made our previous CPU-residing code more explicit. However, it is now also very easy to change the device to a CUDA device:

torch::Device device(torch::kCUDA)

And now all tensors will live on the GPU, calling into fast CUDA kernels for all

operations, without us having to change any downstream code. If we wanted to

specify a particular device index, it could be passed as the second argument to

the Device constructor. If we wanted different tensors to live on different

devices, we could pass separate device instances (for example one on CUDA device

0 and the other on CUDA device 1). We can even do this configuration

dynamically, which is often useful to make our training scripts more portable:

torch::Device device = torch::kCPU;

if (torch::cuda::is_available()) {

std::cout << "CUDA is available! Training on GPU." << std::endl;

device = torch::kCUDA;

}

or even

torch::Device device(torch::cuda::is_available() ? torch::kCUDA : torch::kCPU);

Checkpointing and Recovering the Training State¶

The last augmentation we should make to our training script is to periodically save the state of our model parameters, the state of our optimizers as well as a few generated image samples. If our computer were to crash in the middle of the training procedure, the first two will allow us to restore the training state. For long-lasting training sessions, this is absolutely essential. Fortunately, the C++ frontend provides an API to serialize and deserialize both model and optimizer state, as well as individual tensors.

The core API for this is torch::save(thing,filename) and

torch::load(thing,filename), where thing could be a

torch::nn::Module subclass or an optimizer instance like the Adam object

we have in our training script. Let’s update our training loop to checkpoint the

model and optimizer state at a certain interval:

if (batch_index % kCheckpointEvery == 0) {

// Checkpoint the model and optimizer state.

torch::save(generator, "generator-checkpoint.pt");

torch::save(generator_optimizer, "generator-optimizer-checkpoint.pt");

torch::save(discriminator, "discriminator-checkpoint.pt");

torch::save(discriminator_optimizer, "discriminator-optimizer-checkpoint.pt");

// Sample the generator and save the images.

torch::Tensor samples = generator->forward(torch::randn({8, kNoiseSize, 1, 1}, device));

torch::save((samples + 1.0) / 2.0, torch::str("dcgan-sample-", checkpoint_counter, ".pt"));

std::cout << "\n-> checkpoint " << ++checkpoint_counter << '\n';

}

where kCheckpointEvery is an integer set to something like 100 to

checkpoint every 100 batches, and checkpoint_counter is a counter bumped

every time we make a checkpoint.

To restore the training state, you can add lines like these after all models and optimizers are created, but before the training loop:

torch::optim::Adam generator_optimizer(

generator->parameters(), torch::optim::AdamOptions(2e-4).beta1(0.5));

torch::optim::Adam discriminator_optimizer(

discriminator->parameters(), torch::optim::AdamOptions(2e-4).beta1(0.5));

if (kRestoreFromCheckpoint) {

torch::load(generator, "generator-checkpoint.pt");

torch::load(generator_optimizer, "generator-optimizer-checkpoint.pt");

torch::load(discriminator, "discriminator-checkpoint.pt");

torch::load(

discriminator_optimizer, "discriminator-optimizer-checkpoint.pt");

}

int64_t checkpoint_counter = 0;

for (int64_t epoch = 1; epoch <= kNumberOfEpochs; ++epoch) {

int64_t batch_index = 0;

for (torch::data::Example<>& batch : *data_loader) {

Inspecting Generated Images¶

Our training script is now complete. We are ready to train our GAN, whether on

CPU or GPU. To inspect the intermediary output of our training procedure, for

which we added code to periodically save image samples to the

"dcgan-sample-xxx.pt" file, we can write a tiny Python script to load the

tensors and display them with matplotlib:

from __future__ import print_function

from __future__ import unicode_literals

import argparse

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import torch

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("-i", "--sample-file", required=True)

parser.add_argument("-o", "--out-file", default="out.png")

parser.add_argument("-d", "--dimension", type=int, default=3)

options = parser.parse_args()

module = torch.jit.load(options.sample_file)

images = list(module.parameters())[0]

for index in range(options.dimension * options.dimension):

image = images[index].detach().cpu().reshape(28, 28).mul(255).to(torch.uint8)

array = image.numpy()

axis = plt.subplot(options.dimension, options.dimension, 1 + index)

plt.imshow(array, cmap="gray")

axis.get_xaxis().set_visible(False)

axis.get_yaxis().set_visible(False)

plt.savefig(options.out_file)

print("Saved ", options.out_file)

Let’s now train our model for around 30 epochs:

root@3c0711f20896:/home/build# make && ./dcgan 10:17:57

Scanning dependencies of target dcgan

[ 50%] Building CXX object CMakeFiles/dcgan.dir/dcgan.cpp.o

[100%] Linking CXX executable dcgan

[100%] Built target dcgan

CUDA is available! Training on GPU.

[ 1/30][200/938] D_loss: 0.4953 | G_loss: 4.0195

-> checkpoint 1

[ 1/30][400/938] D_loss: 0.3610 | G_loss: 4.8148

-> checkpoint 2

[ 1/30][600/938] D_loss: 0.4072 | G_loss: 4.36760

-> checkpoint 3

[ 1/30][800/938] D_loss: 0.4444 | G_loss: 4.0250

-> checkpoint 4

[ 2/30][200/938] D_loss: 0.3761 | G_loss: 3.8790

-> checkpoint 5

[ 2/30][400/938] D_loss: 0.3977 | G_loss: 3.3315

...

-> checkpoint 120

[30/30][938/938] D_loss: 0.3610 | G_loss: 3.8084

And display the images in a plot:

root@3c0711f20896:/home/build# python display.py -i dcgan-sample-100.pt

Saved out.png

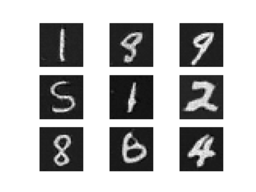

Which should look something like this:

Digits! Hooray! Now the ball is in your court: can you improve the model to make the digits look even better?

Conclusion¶

This tutorial has hopefully given you a digestible digest of the PyTorch C++ frontend. A machine learning library like PyTorch by necessity has a very broad and extensive API. As such, there are many concepts we did not have time or space to discuss here. However, I encourage you to try out the API, and consult our documentation and in particular the Library API section when you get stuck. Also, remember that you can expect the C++ frontend to follow the design and semantics of the Python frontend whenever we could make this possible, so you can leverage this fact to increase your learning rate.

Tip

You can find the full source code presented in this tutorial in this repository.

As always, if you run into any problems or have questions, you can use our forum or GitHub issues to get in touch.